Plex: 18 October 2023

Fixing our Food System; Monocrop Farmers to Biodiversity Restorers; NeoBooks Needs Your Help; Dent 2023; Antidote for “Techno-Optimist Manifesto”; Toward a Civilizational Perspective; Sunset With Sailboat; The Limits of Our Current Worldview, If War Worked, We’d Have Peace By Now; Among The Redwoods

The Biweekly Plex Dispatch is an inter-community newspaper published by Collective Sense Commons on first and third Wednesdays of each month. Price per issue: 1 USD, or your choice of amount (even zero).

In This Issue

- Fixing our Food System: Regen Ag Summit, 10/20-22 on Zoom (David Witzel)

- From Monocrop Farmers to Biodiversity Restorers (Chochi Iturralde)

- NeoBooks Needs Your Help (Jerry Michalski)

- Dent 2023 (Julian Gómez)

- Antidote for a “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” (Peter Kaminski)

- Toward a Civilizational Perspective (Douglass Carmichael)

- Sunset With Sailboat (Jack Park)

- The Limits of Our Current Worldview or If War Worked, We’d Have Peace By Now (Ken Homer)

- Among The Redwoods (Ken Homer)

Fixing our Food System: Regen Ag Summit, 10/20-22 on Zoom

by David Witzel

Here's an upcoming event that GRC folks are organizing:

Enjoy speakers including Lush Prize Winner Bemeriki Bisimwa Dusabe from Uganda, Joshua Hughes in Costa Rica, Fabricio Muriano in Brazil, and Ñawi Flores in NYC.

Our speakers are humanitarians, small-scale permaculture educators, long-term land stewards, indigenous agricultural consultants, ethical fundraising educators and more from around the world.

Participants will learn about and build skills around: local/international market creation, bioregional coalition building, ethical/equitable fundraising, land stewardship vs management and more.

Events include: keynote panels, interactive panels on land stewardship, education and funding, a Regeneration Pollination Session, practitioners session and an elevator pitch workshop with seasoned advisors!

Learn more here and register here.

Please share the invite.

charles blass

From Monocrop Farmers to Biodiversity Restorers

by Chochi Iturralde

(Ed. note: Chochi visits with us by way of Wendy Elford)

When I arrived in Mushullakta four years ago, I had a single mission in mind: to persuade local farmers to become biodiversity restorers. My success has gone beyond my expectations, but not for the reasons I initially thought would bring about the change. The magic came from elsewhere.

Mushullakta is one of hundreds of communities in the Amazon Rainforest of Ecuador; one of thousands if you count other Amazon countries. Like most of these communities, Mushullakta depended on natural resource extraction for their survival. Timber, mining, monocropping, and cattle raising are the only ways people can make an income in these remote areas, and our modern world has incentivized extraction for so long that it has become part of the people’s identity. It’s the sad story of “lack” they’ve heard others say about them for decades. It’s the story most communities tell themselves still.

That is until they hear a different story.

I didn’t see this at first, but like all humans, the people in Mushullakta longed for a sense of belonging and significance. They wanted to be seen, to be part of something bigger than themselves, but they couldn’t escape the oppressive system of social castes and economic injustice that was forced upon them centuries ago. So, naturally, when they were offered the opportunity to renounce that system and become important restorers of the ecosystems needed to sustain all life on Earth, they immediately felt a calling.

To my amazement, their new identity began to work its magic, immediately and permanently transforming their mindsets and behaviors. They became environmentally-conscious, proud entrepreneurs that were contributing to society by resurfacing and applying the knowledge passed down to them by their ancestors, the same knowledge that kept the rainforest alive for millennia.

I thought the extra income would be the main driver of change, yet it was just an added bonus. More importantly, their added income felt like a fair exchange for offering essential services to the planet, not a donation to those who lack money.

This magic showed me that what drives change are stories of abundance and true partnerships, not money. This magic helped me see the simple and effective solution hidden in plain sight: if we give vulnerable communities the opportunity to take the lead on solving our environmental crisis, they can restore our planet’s biospheres much faster and without spending on expensive technology. A win-win like no other.

Chochi Iturralde is Founder and CEO of Humans for Abundance.

charles blass

NeoBooks Needs Your Help

by Jerry Michalski

The NeoBooks project could use your help.

Klaus has a book coming together that features soil, water, regenerative agriculture, Spiral Dynamics and Theory U.

The NeoBooks project could use an extra pair of eyes (attached to a brain :) to read it for continuity and logic (vs line editing, for example). If it doesn't feel like a book yet, what would make it more like one?

At the moment, this is a volunteer role. If you're interested, please ping Jerry.

Dent 2023

by Julian Gómez

Continued from Ellen Bradbury Reid's tour in Plex: 4 October 2023, “... and what was the area called Bathtub Row?”

General Groves’ mechanism for dealing with stress

Whenever he got stressed, “he would pop a Whitman’s chocolate into his mouth.”

A comment about the Oppenheimer’s house

“It was a surprise when the Oppenheimers got a kitchen, because everyone knew Kitty didn’t cook.”

And that the roads between Santa Fe and Los Alamos, and around the lab, were terrible. She said many of the wives expressed a sentiment that they would not venture on the road to Santa Fe again until the war was over.

I agree. To this day the old road between Santa Fe and Los Alamos is absolutely terrible.

But now there’s a freeway.

And this was directly related to how the road to test site TA-10 got paved

An atomic bomb needs a conventional explosive to slam the sub-critical masses together, so there was quite a bit of experimentation going on at Los Alamos to find the best way to do that. In TA-10 they experimented with lots and lots of high explosive, trying to find the right way to trigger the nuclear reaction.

LANL is high up in the mountains, and there are a number of flat ridges extending outward from the central site:

https://maps.app.goo.gl/YydAskBNGDW8qRxU7

(apologies for the advertising, I don’t know how to get Google to not do that)

TA-10 was on one of those ridges, pretty far away from the central site. After all, nobody would've liked high explosives continually going off near the dining hall. The state of the road from the lab to TA-10 was comparable to the state of the road from Santa Fe–terrible. In fact, the road to TA-10 was worse because it wasn't even paved. Imagine being the driver of the truck that was daily carrying all that high explosive out to the test site over a route that dated back to probably the Stone Age.

According to Ellen, somebody finally figured out how to fix that situation. They took the springs off a jeep and convinced General Groves to do an inspection of TA-10 using that jeep. Shortly after that experience, the road got paved.

And what was the area called Bathtub Row?

As the Manhattan Project got going, housing was built at a furious pace. It was impossible to build homes for every single family. There were a few, but then the attractiveness of each abode would be related to how many points a person had. The top management, for example, had enough points to get a house to themselves, one step down would get one side of a duplex, etc. Down at the bottom would be what were essentially bunkhouses.

The street is still called Bathtub Row. It was called that, because–those were the top-ranked houses. They had bathtubs. Everywhere else just had showers.

https://maps.app.goo.gl/m3VnJ92ZZPr1DXGt6

Photos

charles blass

Antidote for a “Techno-Optimist Manifesto”

by Peter Kaminski

Marc Andreessen wrote a “Techno-Optimist Manifesto,” for which some of us might need an antidote. I like Vesna Manojlovic's short note, via nettime-l. The typography isn't as pretty as Andreessen's, but the message is more wholesome.

Manojlovic includes links to additional resources sprinkled throughout her email.

Nettime-l recently moved servers and their published subscribe link is broken. I think this is the new one: https://lists.servus.at/mailman/listinfo/nettime-l

charles blass

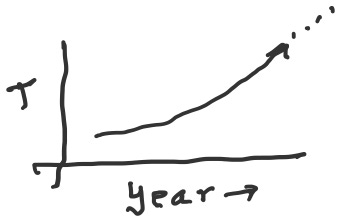

Toward a Civilizational Perspective

by Douglass Carmichael

October 1, 2023

In the early millennia, the few humans lived in families on the surface of the earth, hunting, eating reproducing – and moving around to find food and mates. They also dreamt, invented myths, handled fire, made tools, clothing , cooking and kinship systems. With evenings by the fire, looking at the night sky.

These families grew into tribes and the tribes bumped into each other. Sometimes cooperative, sometimes competitive. They discovered the value of planting - for ceremonial purposes and the burying of the dead. Then they realized seasonal growth meant more food.

They discovered coal and started mining. Then oils and pumping. They pulled these out of the ground and burnt them in machines making interesting things, with the heat such as blades and necklaces. But also what was burned turned into pollution, especially co2. What was under the surface is now above the surface.

What went into the air stayed there, making a blanket that traps heat, raising the temperature of the Earth.

Family became tribes (Polis), it became empires and civilizations, much more diverse than later nation states. (This is from Toynbee’s Study of History and amplified by the Dawn of Everything.)

Of the current world Toynbee said there have been approximately 23 civilizations, five of which still exist. Some disappeared, some collapsed and became new civilizations. The current world:

West. Islam. Hindu. Far East. Orthodox

A few nuances: Far East includes China, Japan, and Korea. Orthodox Christians ss Russia and the Balkans. Each current civilization is the follow-on to past civilizations. One of the best documented examples starts with Mesopotamia and goes on to Sumer, Minoan, Athens, Hellenic, Rome, West.

We also have failed or static civilizations that often led to new civilizations. The aborted include Celtic, Egypt, Hittites, Greek, Sumer, Akkad, Hellenic, Incan, Buddhism, Orphism, Babylonian, Andean, Yucatan, Mexica, Mayan, and perhaps, Polynesian, Eskimos, and nomads.

Some sidenotes:

As the Egyptians took their excess wealth into the pyramids, the west took that wealth into the military – industrial complex and consumer, private pyramids.

With increasing population, Greece was under pressure. Sparta responded by conquering neighbors while Athens responded by colonizing by ship at great distance. The first failed, the second has been fruitful. Athens went on to be the core of Hellenism, which became the core of the Roman empire..

We in the west tend to hide from ourselves the fact of existing other civilizations. All five of the current cultures have atomic weapons and the simple five civilization diagram helps explain the dimensions of current tensions there are many primitive, societies that came earlier, but evidence is scant.

The west can be divided, not into civilizations, but phases:

- Western I Dark ages 675-1075

- Western II Middle ages 1075–1475

- Western III Modern, 1475–1875

- Western IV Postmodern 1875 –?

Whither next?

Our standard way of thinking is in terms of material things that change. Energy, transportation, buildings, roads, knives, and forks, computers, tables and chairs. What we are mostly missing, is thinking about the Social things: political parties, media content, legal systems, patterns of sociability, and civilizations and belief. Toynbee says that we confuse nation states with civilizations. This is important to because change in the nature of a civilization is much more profound and impactful than changes in nation states. For example, when leaders lose faith in the project they are leading the people will rebel. The loss of faith is civilizational, not out of a nation state.

The reaction to climate change is going to be civilizational, moving things by attitude and belief, not by law and regulation, the tools of states.

“On this showing, the nature of the breakdowns of civilizations can be summed up in three points: a failure of creative power in the minority, an answering withdrawal of mimesis on the part of the majority and a consequent loss of social unity in the society as a whole.” ~ Toynbee.

Sunset With Sailboat

by Jack Park

A sunset with sailboat looking towards the Philippines from Kona.

charles blass

The Limits of Our Current Worldview or If War Worked, We’d Have Peace By Now

by Ken Homer

Wikipedia estimates the total number of people killed in wars throughout all of human history ranges from 150 million to one billion. Personally, I’m more inclined to believe the higher end of that estimate is accurate, especially since few people recognize that the genocide of Indigenous Peoples the world over in the last 500 years is ongoing and has likely claimed at least 200,000,000 lives in the America’s alone.

One billion people killed in wars. Ponder that for a moment. It’s a staggering figure!

One billion people have met violent deaths at the hands of people intent on ending their lives. And vast numbers of those people were not combatants but “collateral damage” –militaryspeak for civilians. That’s a helluva social pathology at work! Why aren’t more people working on eradicating the cause instead of addressing the symptoms?

It took from the emergence of the genus homo ±3,000,000 years ago until 1800 BCE for the human population to reach one billion. And in the intervening 223 years wars have killed off an equal number of souls. Why do humans who refuse to grant other humans the right to exist continue to secure positions of power and convince their followers that wars are necessary? And why do people keep believing in that failed approach?

Fifty million people were killed in WWII alone which, according to some, was “the last good war,” whatever the hell that means.

“We’ve tried everything possible and none of it has worked. Now we must try the impossible.” ~ Sun Ra

Recently, I shared a poem on an OGM call that I wrote a few years ago entitled: If War Worked, We’d Have Peace By Now. As news of the hot wars raging in Ukraine and Israel intrude into my awareness, I find my thoughts turning once more to the impossibility of war bringing about a lasting peace. I believe Sun Ra is right. It’s time to boldly try the impossible!

As you read what follows be on guard for the roadblocks your mind is bound to throw in the way. Chances are good that you find thoughts like: “That’ll never happen or, no way that’ll will take place or, good luck with that!” are bound to arise. Consider that those thoughts are not the limits of the world, but rather the limits of your worldview.

“Each person takes the limits of their own vision to be the limits of the World.” ~ Arthur Schopenhauer

Moving up a fractal level from individual to social, I’d expand Artie’s assertion to include that cultures also take the limits of their vision to be the limits of the world. Why not see the limits of what a person or a culture sets as the limits of the world as an entry point where what is impossible can intervene and begin to reconstitute those limits in ways that open new options for relating? To be clear, I’m referring to the limits of how us-humans conceptualize our Human-to-Human relationships. Us-humans also need to revision the limits of the Human-Earth relationship, which will also require a healthy dose of trying the impossible if us-humans wish to save our collective asses, but I’m going to focus on war for the moment which is in the domain of Human-to-Human.

What if those who hold beliefs such as war will somehow secure lasting peace, or that peace is impossible because there will always be threats that can only be addressed by wars, are simply bumping up against the limits of the socially constructed worldview that they grew up inside of rather than breaching the limits of what is possible for humanity? Might that be a lever for prying the lid off the paint can and allowing a different kind of thinking and a “new world order” to emerge?

It can be helpful when attempting the impossible to remember that most social advances were considered impossible at the time they were first proposed. Abolish slavery? Impossible! Give women the right to vote? Impossible! Get rid of lead in gasoline? Impossible! A truly great idea that speaks to improving the human condition will, with time and traction, become reality. It’s much easier to think about and try the impossible if you are dwelling in the long now than if you are consumed by the immediate present.

Here are my four impossible suggestions for creating the conditions for a war-free future by repurposing the world’s militaries:

- All countries with military budgets will be required to spend 50% of that budget ensuring that hungry people are fed, thirsty people have water, shelterless people are housed, and public infrastructure is maintained and upgraded – all things that will produce meaningful work. Remember econ 101 – guns and butter!

- All countries with military budgets will be required to spend 25% of that budget on climate change adaptation and remediation. Climate change is a threat to the security of every nation. Investing military dollars in this way will provide a generous ROI.

- All countries with military budgets will be required to spend 15% of that budget on developing an army of elders who will be armed with food and blankets and trained in mediation techniques and will be first people to visit hot conflicts to listen to the complaints of the disgruntled and offer advice for deescalating conflict and restoring harmony among people.

- The remaining 10% of the military budget can be used for training on how to rescue people from the inevitable natural disasters that will increase due to climate chaos.

Clearly all these suggestions are impossible under the current economic-political-social paradigm. However, I bet that if the above suggestions were implemented, the conditions that produce wars and the corresponding need for militaries to fight them would soon disappear and a future where humans can design their presence in Earth for millions of years to come would soon* become a reality.

What are your impossible suggestions for securing a viable future for humans, animals, plants, and Gaia Herself?

*Soon = within the next 100 years.

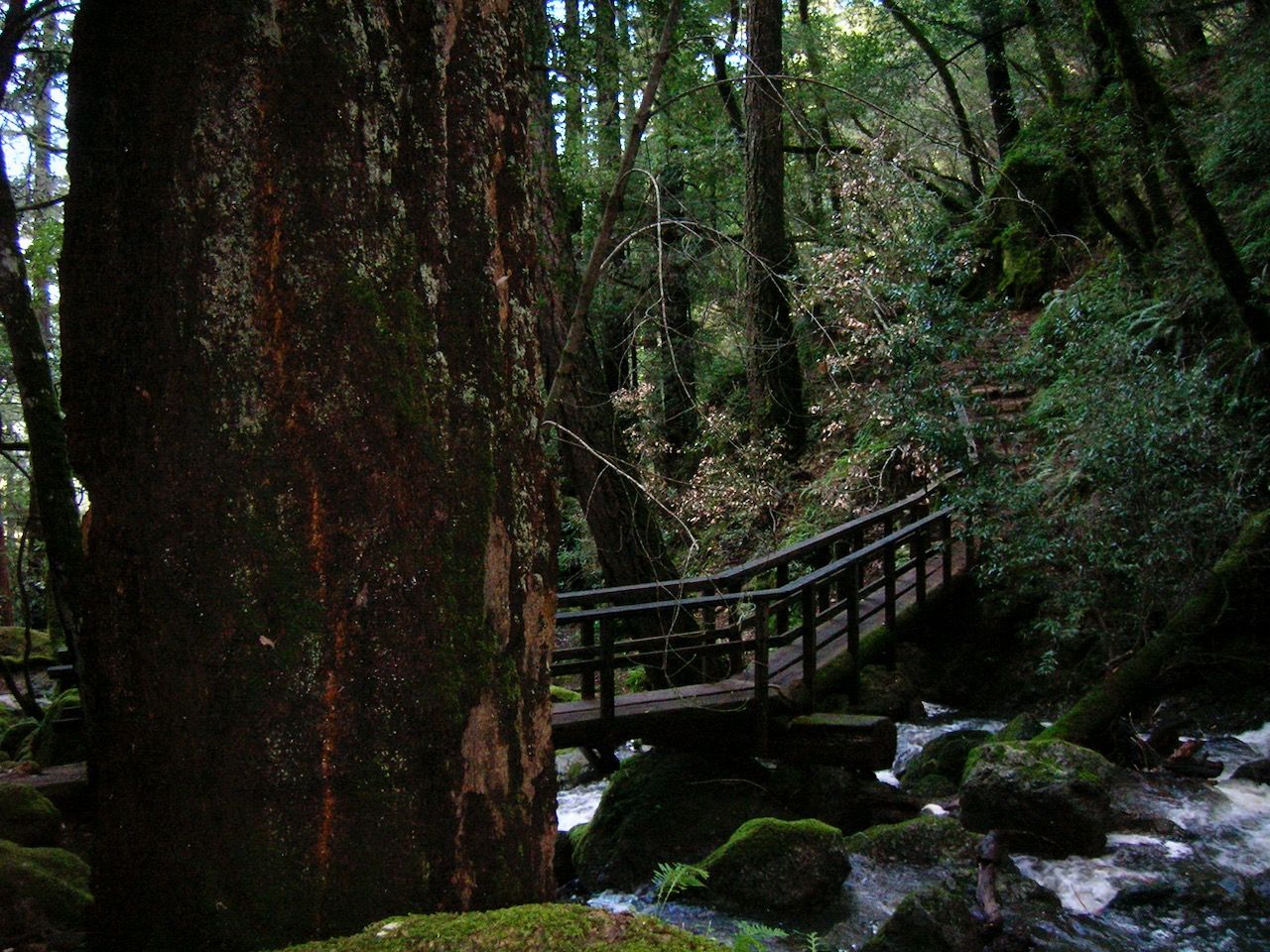

Among The Redwoods

by Ken Homer

A few pix from my hikes in the redwoods.

charles blass

Thank you for reading! The next edition will be published on 1 November 2023. Email Pete with suggested submissions.

Grateful appreciation and many thanks to Charles Blass, Douglass Carmichael, Julian Gómez, Ken Homer, Chochi Iturralde, Jerry Michalski, Jack Park, and David Witzel for their kind contributions to this issue.