Plex: 3 July 2024

Finding Shells; The Deciders; Navigating the Trust Gap; Mirror, Mirror, Tell Me Who I Am; Plex Conversations George Pór, Julian Gómez; Plex Reflection Questions; Why Large Institutions Are Needed to Deal With Climate; Heavenly Hydrangeas; Summer 1980–Bali

The Biweekly Plex Dispatch is an inter-community newspaper published by Collective Sense Commons on first and third Wednesdays of each month. Price per issue: 1 USD, or your choice of amount (even zero).

In This Issue

- Finding Shells (Patti Cobian)

- The Deciders (Todd Hoskins)

- Navigating the Trust Gap (Wendy Elford)

- Mirror, Mirror, Tell Me Who I Am (George Pór)

- George Pór with Peter Kaminski, 2024-07-02

- Julian Gómez with Peter Kaminski, 2024-07-03

- Plex Reflection Questions (Peter Kaminski)

- Why Large Institutions Are Needed to Deal With Climate (Douglass Carmichael)

- Heavenly Hydrangeas (Ken Homer)

- Summer 1980–Bali (Ken Homer)

Finding Shells

by Patti Cobian

March of 2023

I arrived in Costa Rica the way a tumbleweed blows across the plains lining the Rocky Mountains: dry, prickly, cartwheeling along the wind until it slams into a fence, a car, or caught in a front yard. Momentum ceases abruptly, and there it stays until something else comes along to nudge it back into the wind.

My life had felt gritty and sparse for the last two years, and I had a vague suspicion of the cause: I had been running the combines of self-help and therapy through the soil of my mental landscape for five years now (with consistent, deep EMDR and Neurofeedback work for the latter two) in hopes that some of those dense, seemingly immovable patches of dirt and stubborn clumps of hardened ideas might loosen and break up a bit, allowing more air and moisture into the soil. But I could no longer deny it; I was having a hard time recognizing myself whenever I would survey the landscape of my life. Where had the artist gone? When had the play, the delight, the joy disappeared, and who was the thief?

Some instinct had lead me to cease the trauma therapy, though there had been no compelling judgement or discernment to support the decision. After all, the books, the podcasts, the blog posts told the stories of movement, of doing and digging...and this was where the empirical evidence really got to strut its stuff. Statistics like “70% improvement in eight sessions”, blowing more conventional treatment outcomes out of the water with their efficacy and tidy results. Trauma-informed modalities: the leading edge, the promise of a future that might be different from the past, the best hope for those whom little else had worked in the past. I had staked my hope, trust, hundreds of hours of time, training, and several thousand dollars on these claims.

And yet, I couldn’t help but feel that I had little to show for it.

Not long after this unceremonious departure from my EMDR and Neurofeedback sessions, I decided to take a chance: a pilgrimage to Costa Rica, a country that abhorred the very pressures and constraints that I had been laboring under for so long. At 31 years of age, it was my first time leaving the country, and I was choosing to travel alone. I wanted time, I wanted beauty and nature, space and answers. I didn’t know what I would find, but I had some vague sense that something awaited me there, somewhere amid the twenty-nine days that I would be wandering around Los Pargos.

On a cold February evening, lost in a maze of “what-next’s” and “shoulds”, I decided to take a chance, a pilgrimage to country that abhorred the very pressures and constraints that I had been laboring under for so long. I wanted time, I wanted beauty and nature, space and answers. I didn’t know what I would find, but I had a vague sense that something awaited me there, somewhere amid the twenty-nine days that I would be wandering around Los Pargos.

In my effort to honor this month alone of rest and space, I had booked only one call on the entire trip that could be considered a “work call”. It was with a colleague named “D.”, whom I had slowly come to know in a few different virtual community spaces. On one of these calls, I had asked of the group their experience in supporting a client who is struggling to move beyond a victim mentality; D. reached out through a direct message in the chat, saying that he had some thoughts on this and would be happy to discuss further, if I felt so inclined. And so it was that, a little over halfway into my time in Costa Rica, D. and I met for an hour-long zoom call.

I had signed on without any sense of expectation, and more than a little annoyance that I had agreed to schedule a work call during my vacation. By this time, the initial spark of curiosity that had catalyzed our meeting had long since gone out, and I was anxious to resume my new favorite past time in Costa Rica (laying in a hammock so that I could pretend to relax while anxiously ruminating about the state of my life). But now, when I look back on that day, I see that hour as a sharp delineation between my life before that call, and my life after it.

In that one hour, D. had gently and systematically pried apart the trauma-informed framework upon which I stood — built upon a hill I thought I would die on — with deliberate, compassionate hands, and a very quick shovel. As the hour progressed, the rigid architecture of beliefs I had built around that precious framework had collapsed and crumbled at my feet.

We closed the call and I closed the laptop, promptly burying my face in my hands, elbows propped up on that dusty patio table. The sensation of something in my stomach falling away kept my breath shallow, my heart rate elevated; I was thankful to feel the assurance of a sturdy, stable surface.

In my mind’s eye, I surveyed the inner wreckage and splintered timbers: long-buried suspicions that, perhaps, this work might have been helping in some ways, yes, but how much might it have also been harming? After all, I did not feel more resilient or robust, but almost… enfeebled, often shrinking away from the edges of my life that felt too sharp or confronting. On those rare occasions when I would peer down into my creative well, I saw only darkness and dust.

And that’s when I cried, my head in my arms now, table shaking, the weight of this dust and ruin anxious to leave my body.

When I was finished, I sat back up in my chair, wiped my face, and considered what to do next.

I glanced back down into that dark, dusty well and thought, I need water. I need to go play.

Half an hour later, I was buzzing around Los Pargos on a rugged e-bike, stopping to take photos of “for rent” signs whenever I saw them, because I had decided that I was breaking up with the United States of America and wanted to move away as soon as possible.

I knew the area well enough to make sure to take the prettiest roads, even if there was more mud or potholes. I delighted in the violently pink, magenta and purple bougainvillea that laced through the rough, uneven fences and climbed over stucco, popping like fireworks against the earthy tones of this tropical dry forest. These gorgeous flowers — a stunning feature of the Guanacaste region — had quickly stolen my heart and imagination, unceremoniously shuffling “poppies” out of their long-held tenure as my favorite flower.

I laughed aloud as I rode underneath a single, unlikely stalk of bougainvillea that had shot out an extra twelve feet from its bush, dangling comically over the dirt road. The stalk was completely empty and bare for eleven whole feet — until the last few inches, which had exploded into a large bunch of flowers, trumpeting a feisty fuchsia against the cornflower blue sky.

Breezing by a pasture full of the most enormous (and bored-looking) cattle I had ever seen, I banked a sharp right and slowly picked the e-bike down a narrow dirt path and around some trees, finally parking it next to a metal fence. As I locked the bike up, two startled geckos raced up the wire; I must have woken them from their afternoon nap.

The beach was almost empty. It was a smaller, private cove, more secluded than the popular beaches in the area, with enormous beds of volcanic rock that exposed themselves in low tide. Today, maybe eight or nine other people partook of the shore, which was long enough to ensure that everyone had more than enough beach to themselves.

I made my way back down to the sand, feet bare, picking my way along the line of shells that were sprinkled along the shore, as though a box of confetti had been tipped over along the leading edge of the water line. I didn’t stop until I saw a bright blue candy wrapper among some of the shells; automatically bending down to pick it up, I immediately recoiled in surprise: it was squishy.

Looking more closely, I could see that the bright blue, candy-colored blob wasn’t a plastic wrapper — it was a jellyfish. Sadness tugged at the bottom of my heart as I considered its — legs? — buried among the rough, gritty sand: what a hard, coarse ending for a being so soft and fluid.

Staying crouched down, I considered the rest of the shoreline, entranced by the way the water would wash over the shells, taking some back with it, always bringing new ones...and then, I heard it.

It was a sound — a shiny, sparkling, completely new sound, one that I had never heard before: the soft, porcelain tinkling of thousands of small sea shells being tumbled against one another by the waves that washed along the shore. I froze, captivated and waiting, needing to hear it again:

Clink, clink, tinkety-clink clink, shoooshhhh.

Clinkety clink clink, tinkle linkety-clink — shooooossssssshhhh.

The soft trill of this dance between land and sea was hypnotic; I sat down, right there, nestling my hips into the sand. As I began to settle in stillness, I took in the shoreline and was rewarded by yet another novel, natural delight: if I remained still, armies of small, domed shells would come to life and move, their pointy crab legs scootch—scootch—scootching along the sand, picking between other shells. The moment I moved even an inch, they would freeze in unison, becoming as stationary as the other stones and shells around them. The longer I waited, the more of them I could see: dozens of them, all coming to life for a few seconds at a time, risking a few inches — even a couple feet — before stopping to retreat back under their shells.

Beneath the richness of my wonder, I could sense the dry recognition of familiarity. I considered the wisdom of a more measured, sustainable journey, rather than the sprint to the finish line that United States culture seems to endorse across its many metrics of success. I looked up and found the fine line of the horizon, eyes unfocused, and suddenly understood: unless I had stopped, sat down and become still enough — content with merely being and listening — I may never have seen this extraordinary beauty.

I turned my attention to the water in front of me, losing my thoughts among the waves for a time before refocusing down at my toes. As the tide began to rise, the water would occasionally brushing up against my feet and past my hips, bringing with it a swell of sea shells. I was struck by the variety of colors: bright, poppy-pink underbellies, creamsicle-orange and white swirls, beautiful soft, white spirals, purples and violets, and, my personal favorite: watermelon-rind green half-dome shells sprinkled with thin, red lines, each with a hole right in the top and center of them.

Who used to live in there? I had never seen a shell like that before.

And how glossy and smooth they were! Like bits of pastel-colored blown glass; little jewels, all of them, the treasures of the sea, washing up around me.

If I just sat there, present, and waited, the waves would come when they came, and with them, they brought new shells. I didn’t have to stand up, look around and search for them. They simply washed ashore, at my feet, if only I sat and waited long enough.

This was a new experience for me. I’ve always searched for sea shells on the beach; I remembered what it was like as a kid, bag in hand, headlamp if it was dark, the thrill of the search and digging…it had never even occurred to me that there might be another way to do it. Settling back in to the rhythm of the swell of salty water, another understanding materialized, simple and clear:

When I do things, often, it’s because I don’t trust that they’ll get done unless I do them myself.

… Huh.

Yep. That tracked.

I began to scoop up handfuls of sand onto my feet, building a mound of earth around them, enjoying the feeling of the heaviness, the warmth, a part of me recognizing that I was building this because I wasn’t about to go anywhere, which felt delightful. I settled back into the steady rhythm of Playa Blanca, its warmth, the breeze, the water sighing up and down long lengths of sand and the musical symphony of millions beautiful sea shells waxing and waning along the shore. The dust clouds that had arisen within my heart as the Known and Certain collapsed seemed to have disappeared on the breeze; I could breathe again, and I could see more clearly.

Perhaps the Frameworks and Pathways, the Known and the Quantified are never quite as stable as they seem. I began to wonder if maybe it wasn’t me that was the problem; perhaps the problem arises when we try to “fix” our idiosyncrasies and protections, scars and destructive adaptations, by forcing them into these stale, static frameworks?

Is the first misstep taken when we mistake a stepping stone for the finish line?

Have we forgotten that we, humans, are Nature too — Life itself — undulating and unfolding, emerging and evolving in its own brilliant perfection? What if the human condition wasn’t the problem after all? What if the intricate inventions of the psyche, erected by mind and nervous system to protect our hearts and bodies from threat and pain — while inconvenient and often troublesome — are working in favor of our evolution, and not against it? What if, this whole time, we’ve just been reading the river wrong?

I thought of the long, wandering path of healing — the digging and excavating, the intensity of long-buried emotional releases that shake window panes as they’re finally freed from a human body. I thought of the searching and striving and the blind leading the blind, the hunt for the pain that is booby-trapping the lives that we are trying so hard to build for ourselves, the ever-moving goalposts and new data and new modalities and promises that this framework will take care of it, this will be the thing that neutralizes the brilliance of evolution. We’ve done it — we’ve finally outsmarted it — and now, we can conquer it.

I thought of the Ticans, the native Costa Ricans who lived here in Los Pargos, outliving the rest of us with their slow living, loose schedules and unfinished roads that, season after season, would spook the particularly calcified American tourists right back into the systems of efficiency and striving that they had spent their carefully planned vacation trying to escape from in the first place.

If we are conditioned to know strife, will ease seem like the bigger threat?

The shells continued to wash up around me, unbidden, unhunted. I thought of the many times that Life had done same, washing up long-buried grievances or painful memories in chance occurrences at grocery stores, or while watching movies, or trying to understand a loved one, or on my honeymoon, or smelling flowers at a farmer’s market, or right before a big presentation. How frustrating and unfair those invitations had felt in the moment — how dare they? Why couldn’t they just leave me alone and let me enjoy my life?

But this is what I have found: Life brings us these opportunities for healing and resolution often and unexpectedly. Do we refuse them because we didn’t ask for them? Or because we’ve been taught to see these moments as inconveniences and injustices, bad luck or God’s wrath or some kind of karmic recompense for some forgotten deed?

As I buried my feet more deeply into the sand, a gush of salty water rushed over the mound I had so carefully created, washing away my efforts with no apology. My painted toes stuck out of the sand once more, glinting wet in the sunshine. For all of the recent tumult and collapse, something was emerging from the wreckage; it wasn’t another structure, but rather, a living, breathing idea, a singular expression of the Life that was, in that moment, doing its best to move through me:

We cannot contain Life in cages, nor can we pin Life down into static frameworks. Life will always break free of our attempts to bind it, to measure and quantify and bend Life itself so that it might protect us from the weight of our own existential fear and insecurity. We try, and when Life refuses to play ball, we end up with our heads on picnic tables, crying as those structures that never really even belonged to us crumble, and we have to start all over again.

Now, one year and three months later, I look back on what grew from the wreckage of that inner collapse and I feel the promise of what has grown in its place: something more fluid, more flexible and free. In my own system, it feels easy to trust the natural cycles of death and rebirth.

Now, one year and three months later, I look forward into the collective, and it feels far less easy to trust the natural cycles of death and rebirth when it is so easy to imagine the dust and the wreckage that looms: the barren soil, the hungry humans, the skies empty of birdsong and bee.

I wonder if we will try to find our shelter beneath the crumbled remains of those shining, empty promises of innovation, convenience and equity for all?

In my heart, I wonder what may have been — and, perhaps, what may still be — if we all refused to wrestle the Nature within us into subservience, to beat it into submission, or to twist and contort it into man-made delusions.

I stand before the coming wreckage, and I feel the grief of a planet who is waiting for us to remember.

The Deciders

by Todd Hoskins

I grew up in a family where my dad was in charge. In addition to being a basketball coach who learned from “The General” Bobby Knight, he was a Deacon in our church. He dispensed discipline to college kids who didn’t get back on a fast break, to members of the church who were living in sin, and to me and my brother when we were “out of line.”

My dad was more than a disciplinarian. He was the decider. I can now see that he didn’t always like that role but felt he was obligated to fulfill it. "For the husband is the head of the wife as Christ is the head of the church,” writes the Apostle Paul in the book of Ephesians.

Buried in the commentary around the US Supreme Court’s decision on presidential immunity is the legal philosophy that has gained prominence in the Federalist Society, and likely guided the majority on their decision.

Unitary executive theory proposes that executive power be centralized in the President, rather than shared with other executive agencies or Congress. This theory argues that the President, as head of the executive branch, has broad and largely unchecked authority over the executive functions of the federal government. Many believe–even outside of Christianity–that we need a decider.

Lawyers in the Reagan administration were the first to argue this was necessary for a well-functioning government. Dick Cheney became a vocal advocate, especially after 9/11. Since then the idea has quietly gained momentum in conservative legal and political circles.

I don’t believe (at least most) of the Supreme Court justices were simply trying to set the stage for a specific favorable future as they see it. They have a distinct view on what effective leadership is, and fear that without the clarity, efficiency, and simplicity of someone on top of the pyramid, there is no “forward” movement.

The current CEO-to-worker pay ratio for S&P 500 companies is 272-to-1. The CEO to CFO pay ratio is more than 2-to-1. You can hear the shareholders saying in one form or another, “We don’t need just a strong leadership team. We need THE guy (and it’s usually a guy) leading that team.” The organizational world (including nonprofits) believe we need a decider.

A leader retired at one of my client’s organizations. With no heir apparent and no budget to add to the head count, I introduced a shared leadership model that I thought could work for them. After two months of easing into it, I realized I was moving too fast. They did not trust it could work because they hadn’t seen anything like it before.

This is more than the legacy of monarchies and monotheism. It’s more than just our iconic individualism. When we become so singularly focused on how we humans organize and mobilize, without regard to the rest of Nature, we lose our imagination.

We get rigid hierarchies and unitary executive theory not just because certain people are trying to grab power, but because people don’t believe shared leadership is effective or possible.

This is on all of us. In order for people to see new futures, we need new experiences. We need to feel shared leadership working, not as a theory, but as something that impacts us on a day-to-day basis.

I’m a big fan of co-operatives, Sociocracy, consent-based decision-making, and other tools, models, and practices that can support the sharing of power. The architectures of participation exist. They are not enough. We need more imagination if we’re going to collectively become the deciders.

Navigating the Trust Gap

by Wendy Elford

For the longest time I’ve been interested in what is called ignorance-based learning. However, naivety is not a pretty place to live, just a reasonable place to start and a perspective to take on from time to time to keep the beginners mindset active in a massive world.

There’s such a fascinating number of options to pursue at the moment if you’ve had a fairly broad and storied career and you’ve got your eyes wide open to some of the ways in which the world is changing quickly right now.

So as a frame for this conversation, I like to keep myself in two places, two types of worlds at once. The first is the community sphere where people help each other and there is generosity, so much cherished open software and honest conversations. I treasure this honesty in dialogue with people open to self knowledge and learning. These dialogues lead to real change in peoples lives. The second place is one where people who have power of different sorts – think politicians or designers or business leaders – need to make enough sense of the world to be able to make decent decisions quickly enough. Decisions that are relevant for their business and allow them to move forward in a very fast changing world.

So for all of my sins here am I stuck in the middle between two worlds and choosing to be there. Decoding one for the other is a piece of evil that has become my specialty .Since I’ve been using the equivalent of large language models for the best part of two decades in some form another, I do have something to contribute here. After all I’ve seen and experienced from a human and personal development perspective I have come to believe that we are all just trying to hold our own. Even if we do push a little evil, even a lot of evil on each, as we do hold our own, we do need to allow each other a moment’s thought or connection to understand what ‘holding our own’ means for the other person. Which warrants another whole post entirely.

So what does that mean for me as I do legal work and design work and work with communities to build local ‘capital’? And more challenging times with people who are inside much larger entities like large corporate or governments?

The first insight really is that I need to be super clear that everything that I do means I don’t breach trust. If I’m going play with newer technology, I need to be really clear that at first I do know harm as I learn and apply what I know in the different worlds I mix in to ensure I am useful, that I provide value.

So what is today’s work? Today is a day when I work out how vulnerable I am in playing with large language models that are free to air in the open space like OpenAI, Gemini and friends. To wage a personal war of sorts between the lockdown in my own personal world that limits what leaks out from my computer and tech use, yet still be open to ways to work with outside influences and new stellar tools and ways of working. At every turn there are new challenges and threats. New tools to learn to integrate or to be deaf to.

I owe this security mindset to the people that I work with whether they are on the public benefits side in terms of community or on the for profit side. (Note to self - if you think of government is making a profit or large corporate as making a profit there is always money rolling around there somewhere in the power spectrum. Someone who always needs to have the upper hand to make their own particular world turn just another day, no matter how painful that turns out being for other people). There are in-between spaces and plenty of them between major players, but those two to three mindsets are the ones that I’m choosing to serve so that I can work out who is who in the messy middle.

And really this is going to come down to what I’m prepared to pay for, what I’m prepared not to allow for in terms of my personal energy to invest in, what I am setting up as my values. And the technical fence around my own little piece of work sitting here at my computer, Internet on or off with all of the applications I’ve chosen to use and all of the connections that I’ve made and all of the vulnerabilities that I’ve created over time by attempting to work in a very open way. A very authentic way and often a very effective way. And in trust.

In less than an hour’s time, I expect to be making a little progress here. It’s almost like going to a confessional in a church to say here are my sins. Here are the things that I should have done better. Could have done better if I had known what I know now. Help me fix up those gaps at least where the critical issues lie. Let me see what I have refused to see up to this point. I hope that it means that I can really start to get to grips with what I can honestly, hand on my heart, promise to people when their trust is the highest value that I need to place on our relationship. And to do that I need to have someone have a real critical look at how I operate.

This is going to be pretty exciting and perhaps very scary.

It’s a little bit like going in for a full health check after you’ve been ignoring lots of aspects of your health for many decades. And it needs to be done so watch this space.

Mirror, Mirror, Tell Me Who I Am

by George Pór

This is the introductory section of George's work-in-progress book, titled Will the Superorganism Be Sovereign and Metamodern?

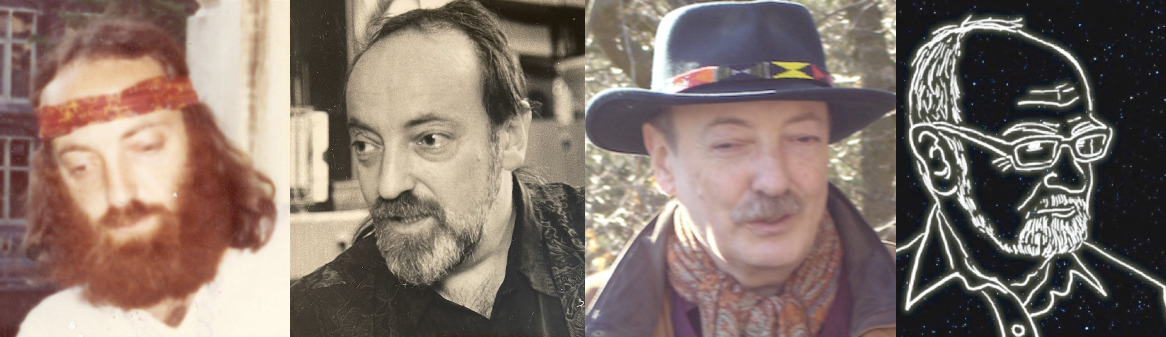

I met a hippy, a hacker, a hermetic, and, more recently, a hipster. When I looked into the mirror, sometimes one, sometimes the other looked back into my eyes. I recognized those characters in my life and what connects them only after reading Hanzi Freinacht’s The Reign of Hackers, Hipsters & Hippies.

Like many of my generation's hippies, I went to India in the ‘70s, seeking truth in meditation and sacred sexuality. That trip turned me into a meditation teacher but didn’t extinguish the “social justice” flame in me, which animated my student years in the '60s.

Returning to the West and running out of money, I found a job in a computer store in Oakland and started experimenting with how one can use the then-fledgling computerized bulletin boards and online networks to create more democratic workplaces by augmenting the employees’ collective intelligence. As a columnist at a magazine in California in the ‘80s, I wrote about the socially innovative uses of computer-based communication. That earned me the “hacker” reputation and an invitation to the Hackers Conference, although I haven’t written any line of code.

After the left-to-right brain move of my life (from a hippie to a “hacker”), the pendulum of the journey swung again back to the right-brain world, this time to the world of a hermetic. I can’t forget the scary and exhilarating experience, around 1992, in the Santa Cruz Mountains, of sitting in the pitch black inside of a sweat lodge and chanting the Sacred Twenty Count of the indigenous people of North and Central Americas, which our lineage holder brought to us. It is an esoteric meaning-making system, a sort of meta-narrative that accounts for 20 archetypal energies of the universe and life on Earth. It also contains the founding wisdom of the Medicine Wheel that I’ve been using since then for patterning my Circle of LifeWork in my annual personal ceremony.

Fast-forward to the beginning of the 21st Century, the beginning of which finds me as a Senior Research Fellow at INSEAD, an international business school in Fontainebleau, near Paris. There, I leverage my theories of online networks, prefigurative social movements, and the cultural capital accrued during my work at UC Berkeley and in the Complexity Research Group of the London School of Economics.

In the ‘20s, I developed new concepts and frameworks that made me a “hipster,” in Hanzi Freinacht’s sense of the word, such as Transformative Communities of Practice, Enlivenment Theory of Change, Wisdom-focused AI, and Collaborative Hybrid Intelligence (CHI) spawning the symbiosis and sympoiesis of human and AI agents.

The last one goes to the heart of my current work, the possibility of a metamodern superorganism emerging from large-scale CHI.

This is the season of my life when I can let all 4 Hs come out, play, and dance with each other. While the perfect storm of our global crises is looming on the not-too-distant horizon, the 4 Hs invite all metamodernistas to prepare for it with the perfect play.

“to deepen the struggle

until it is reborn as play”

— Hanzi Freinacht

George Pór with Peter Kaminski, 2024-07-02

A Plex Conversation

Pete: You’ve said that our median consciousness is lagging way behind our technological development. We seem to be a little stuck. How do we move past that? How do you see that happening? Or maybe a different question is: are you optimistic that we will move past it?

George: Yeah, that’s a beautiful question. What makes it beautiful for me is that it calls for some no-kidding serious introspection. Because from the top of my head, what I say is that I’m not optimistic, I’m not pessimistic, I accept what it is. And by accepting, I don’t mean resigning to it. But being realist, for me, is a kind of utopian realism. And the utopian realism is the pessimism of the mind combined with the optimism of the heart.

Now, that may sound a little bit abstract, but how does that manifest in the life of a person like myself? When I’m thinking about the world situation, I feel there is no way that we can fix that mess before everything collapses and something new may grow out on the ruins of the current world order, of the current civilization. So that’s what I see when I look at the world from my mind.

But I am not only my mind, I am also my heart and my hands that, just because of who I have been in all my life, engaged in bettering the world, doing something that I believe wholeheartedly that in a small way it can make something better. And when I am seeing the world from my heart, what makes this heart connection very alive, not an abstraction, not a metaphor, is my grandchildren.

You know, I’m an old guy, although I feel there is still a good deal of life energy in me, but clearly I may not be around when the sh*t hits the fan. And who will be around is the next generation that I feel we owe something, I owe something. And what I owe is to me to do whatever I can to prepare them.

Well, how can anybody be prepared for the unthinkable, for something that cannot be prepared for? Well, I know only two things, and then I stop after this. I know only that how we are going to come out on the other end of the metacrisis, it depends on really two things. One is how much we are able to host the world inside us, which is the deepest of compassion that we are capable of. And the corollary quality is knowing where my tribe is. Where is my tribe? Where is the relationship with people of mutual trust and caring for each other?

These are the two things that I would like to contribute to creating the conditions for: individual vertical development, and building communities of resilience and co-creation. That’s what I believe that well-crafted and wisdom-guided AI can contribute to. And by that contribution, I mean to help make the outcome of the intention that I described, to help it scale. Because scaling, and scaling it in a timely manner, is obviously pretty important. What I can do by myself is infinitesimally little. So that’s my short answer.

Pete: It’s a very good answer. Thank you. I like how you said you’re not optimistic and you’re not pessimistic. You’re accepting of how the future may unfold, will unfold. That makes a lot of sense.

A way that I think of the future is that collapse may be likely, but that we can do work now and continue to do work that will shorten it and lessen the depth of it. So we can have a great big dip, or a smaller dip and better recovery.

I wonder, for our sixth or seventh generation, when they look back on us and think, well, they tried hard or they didn’t try hard enough at all, or they succeeded, they made a better world for us–what do you think?

George: Well, what I think, what I believe, is less important than what I do. And what I do is strongly influenced by my contemplation of what is mine to do. What is mine to do? Because the world situation and trying to fix it is not mine to do. That’s the context in which I operate. That’s the arena in which I may have a chance to do something very little in whatever is within my capabilities and chance to have an impact, which is, as I said, it’s very little compared to the humongous world challenge.

And I don’t believe that if each of us is doing just this little thing that will add up and everything will be okay. No, it’s not like that. That would be kind of naive, magical thinking. Instead, how I try to shape my own activity is always within what is mine to do, always asking myself which action may have the greatest evolutionary payoff. And of course, I cannot objectively assess that. There is no way to measure in advance the outcome. But with a little systems thinking combined with receiving, tuning my antennas for evolutionary epiphanies, which are the most likely scenarios that will unfold within those scenarios, which are the one that the closest to my heart.

And then that bigger picture informs me how I choose to act according to my capabilities, my resources, my history, my network. So, yeah, I’m not thinking of fixing the world, but definitely looking for the greatest possible evolutionary output to which I have a little chance to contribute. That’s why I am working now with AI, because there is so much hype, mostly spread by the AI doomers, that it will destroy our world. Even [Daniel] Schmachtenberger, a guy who I have high respect for, even he is talking mostly about AI as an existential threat. And I don’t deny that it can be an existential threat, but it can be also an existential hope. Whatever I bring my attention to will grow. And so, I bring my attention to the emancipatory potential of AI.

Pete: I like that. I like how you said that you don’t worry about working on the things that aren’t yours to work on. How do you avoid getting distracted by the things that you wish you could do, but maybe aren’t the highest evolutionary output?

George: That’s a continuous struggle every day. Every day. Because living on the edge comes with the blessing and curse of continually being presented to lots of opportunities to act, to engage with, to act on, and opportunities that are very dear to my heart. And also, opportunities for which I trained myself throughout my life, developed some talents for. Yet, I am very clear that I can do only as much as I can also because of my age. I have less energy for action, for projects than I had 10, 20, 30 years ago.

So how do I handle that? There are two things that help me to choose the right action day after day, not to get distracted. One is a kind of self-oriented listening to what brings me the greatest joy. What kind of action enlivens me? And that’s very important because if it’s not enlivening, then it’s a sign that I’m choosing the wrong thing. That’s one aspect that informs me about what is the right action for me to stick with, to stay focused on.

The other is a trust that there’s a growing number of people who are attuned with what they need to do. And as I said earlier, I wouldn’t settle on the good feeling that everybody does his or her own bit and then it will be all fine. No. So how does this ecosystem of initiatives, movements for civilization renewal, how does that inform my action? Besides the first criteria that I mentioned, what is enlivening for me, actually it’s not besides, within that part of that bundle, it’s also what is enlivening for me is what creates more connections with others. That deepens and widens and multiplies the flow of energy, insights, information, experiences flowing through us, through this informal, loose network of people who are working for change.

So that’s another litmus test for my action that decides that it should be fun. Will it contribute to the flow, the enlivening flow in the world, in my world, in the ecosystem of transformation? Because that’s also part of current reality, that there are millions of people who are working on this or that aspect of planetary transformation. So I just look around and see who are in the adjacent niches, who are the people who are in the neighborhood of this ecosystem, and how my action can connect and amplify theirs. Does that make sense for you?

Pete: It makes a lot of sense, yeah.Also, one of the things I think about is the word “human.” And often people think of that as an individual. Kind of like, “I see a tree, I see a deer, I see a human.” It’s one human. But I think another way to think of “human” is that humanity, being human, is collective action. So the people we were a million years ago or something like that, it wasn’t until we figured out how to work collectively together, and to remember over time, that is when humanity was really born. So you’re saying the things that are most “human” are the things you want to work on, which makes a lot of sense.

George: Beautiful. Yeah. Totally agree.

Pete: It’s always a pleasure, George.

George: Thank you. Have a good day!

charles blass

Julian Gómez with Peter Kaminski, 2024-07-03

A Plex Conversation

Pete: Tell me about Augmented World Expo.

Julian: It was in Long Beach , about two weeks ago, middle of June. The first thing is I'm not sure why it's in Long Beach. It didn't need to be. It could have been many other places like Santa Clara where it historically has been. Apart from that, it's clear that AWE has become the go-to place for modern XR tech. You can expect to see all kinds of stuff there from different kinds of no-code authoring systems to hardcore optics and waveguides using lots of words that even I don't understand. Exposure to the companies doing all kinds of stuff was terrific. Korea actually had two pavilions showing off companies. Taiwan had one pavilion. There were a lot of interesting startups going on there.

The sessions were also useful in getting perspectives from people who have been doing it. I think one of my favorites was the USC reconstruction of the original Chinatown Los Angeles, which was razed to build Union Station back in the late '30s. They reconstructed it from photographs and personal accounts of what the Chinatown looked like. They actually have an AR display that you can go see. It's going to be at Union Station until the end of September, I think. If you happen to be in LA, you can go experience it. I like that one because of the meticulous way in which they recreated a historical context and it showed how to do things properly.

There were a bunch of personal recollections from, as I said, people who were doing things. For example, Tom Furness talking about the work that he did years and years ago developing some of the foundation work for doing VR and AR. Interestingly, I saw a similar note - if you follow Doug Engelbart's career, he created lots of tech that's essential to modern world. I've noticed with people like Doug and others that in the later parts of their life, they started looking towards trying to make society better. I saw the same thing happening with Tom who helped create this Virtual World Society where they're looking at the social aspects of using all of this tech.

I was there for the first 48 hours. I missed the last 12. I think I got the gist of it all because I was able to go through and experience everything I needed. One of the things about XR tech is that you can't just hear about it. You can't just see pictures of it. You have to do it. There were plenty of companies demonstrating different types of gloves. This dates back to the original VPL DataGloves, which had sensors for all of your finger joints. That was the original and there've been lots and lots of attempts at making gloves, which are more lightweight, more accurate, et cetera. Plus experiments with putting things like vibrating crystals at the fingertips to get some haptic feedback.

Actually, the state of gloves has regressed in the last few years, which I find surprising. The state of haptics has not progressed really. The only two possible technologies around are vibrations at the fingertips through whatever mechanisms and then UltraLeap, which uses puffs of air into the hand. I'm hoping that in the research section of the upcoming SIGGRAPH conference at the end of the month, we'll maybe see some more experimental ways of trying to get haptic feedback, because sight and sound are fairly well covered, but humans still have other senses in addition to the way that humans cognitively perceive things beyond the primary five senses.

Overall, AWE is the go-to place if you're into any kind of XR tech.

Pete: Awesome. It's kind of taken over from SIGGRAPH in that respect. Is that right?

Julian: Yes, in terms of products, because AWE is a product expo. It's not a research conference. If you wanted to go and buy something, you'd go to AWE. Even if it's really advanced, just about everything there is at the point where you can buy it right now. Whereas at SIGGRAPH you'll find research and some of these things may not hit the product shelf for another five years, but it's good to know what kinds of ideas are being worked on. Both are important. For someone like me, I'm involved on both sides of it. So I go to both.

Pete: Yeah. Do you want to tell Plex readers a little bit about SIGGRAPH this year or not yet?

Julian: Sure. Although I can't give a comprehensive overview because I've been really nose down in my part of it. I'm in charge of the Retrospective Program. This year I'm focusing on not art history, but computer graphics art history. I have one panel with David Em, Francesca Franco, and Tamiko Thiel. These people are really eminent in computer graphics and in fact, in computer tech. For example, Tamiko designed the Connection Machine. Not the circuitry, but the look of the actual computer. David Em is in the Smithsonian. Francesca is an art historian and curator extraordinaire. I have these three people on one of the panels. Then I have Theodora and Daniel talking about using computation to create art, which is not computer generated art, but rather art where computers were involved somehow. Of course, this applies to everybody, but they've done a lot of research and overview on how that's happening.

Pete: Anything special with SIGGRAPH?

Julian: One thing I'm hoping to have ready at SIGGRAPH is the Center for Computer Graphics History. This is not a museum. It has a multi-line mission statement. The first goal is to get computer graphics history down. In this field, we've lost a whole bunch of people already and we're going to keep losing people. The intent is to get the first person accounts down regardless of the technology. The second goal is research into digital models of history. This quickly becomes a graph database problem when people talk to me about it. In fact, an RDF graph database, because all kinds of abstractions are necessary to represent history. I think this has not been explored because generally historians think about history a lot. They try to make these connections and then they put it all into prose. My contention is that it doesn't need to be prose. I want to see relationships.

An interesting anecdote from my undergraduate career. To graduate with honors, you had to take a special class and write a thesis. The class was conducted by Professor Bill Kahan. If you look into him, he's the primary architect of IEEE 754, the floating point standard. One day in class, I made a comment about the Munich Appeasement and boom, the entire class was all about Hitler and Czechoslovakia, etc. It turns out that he's a real nut on history, especially World War II history. We got a real history lesson that day from somebody who was passionate about it. It was clear, how did this happen? This was a hardcore computer science class. We're talking about the 1939 Munich Appeasement. It became clear many years later that there are all these connections and history is really about connections. We get taught history, like the War of 1812 and these things happen, but there's all this stuff that went into it. The Boston Tea Party wasn't just a bunch of guys dressed up as natives throwing tea into the harbor. There were a whole lot of factors that went into it.

This is why I say it's clear that it's a graph database. That's an easy enough thing to say. But what are the data abstractions that you put into it? One of the good ones I'd like to point out is that any attribute you want to pile into whatever technology you're using, it's actually time dependent. A simple expedient like, what's your name? Well, lots of people use their married names, but they had a different name before that. Whatever attribute you talk about needs to have a time dependency ingrained into whatever the digital model is. That of course means that as you try to query the knowledgebase about this, you're going to have to keep the data abstractions in mind.

The bigger issue is that graph databases get real complex, real fast, and you can't put them on a screen. In fact, you can't put them on anything flat. This is where the XR technology comes in. The idea is that you will be able to use your cognitive abilities to manage and access the knowledge base that is the center's knowledge base. You don't type in queries, you will use your hands, use your eyes, even your feet if you want, but you pick up the knowledge as you would pick up a fork. This will be used both to create and manage, to create the knowledge as it flows in from all the various sources, but also to query it and to try and understand relationships.

I can cite a current reference. If you try it on the Apple Vision Pro, go to the Apple store, you can get a free demo ? One of the things they will have you do is if you want to zoom in on something, you grab space just with your hands like this, move your hands apart. This is how you zoom in on whatever it is you're looking at. This kind of input mechanism was actually developed by Paul Mlyniec 30 years ago at a company called MultiGen, and it's a construct that works. Now imagine you're looking at a complex knowledge base and you need to zoom in on a particular portion of the knowledge base. This is all in virtual 3D using XR displays, not 3D on flat display. You just use your hands and grab this area of knowledge and you can zoom in on it.

Another part of the mission statement for the center is that XR will be the primary mechanism for managing and accessing the knowledgebase. This has relationships to SIGGRAPH because it'll be launched at SIGGRAPH. It has the application to computer graphics because it's a computer graphics history, but also XR. Of course, one of the things that I was doing down there in Long Beach was looking for any technology that would be potentially useful in the center. You see that there's the basis for everything I'm talking about this afternoon in that we go beyond flat. I'm done with flat.

Pete: Nice. Could you tell us a little more about the Center for Computer Graphics History?

Julian: The Center is a California corporation. It's a nonprofit 501(c)(3) and I'm gradually building up the board of directors. Its primary input stream will be through research projects in collaboration with universities. The Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey and UMBC, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, are already signed on. UMBC is interested in the knowledge management aspects and NPS is interested in the XR aspects. Then I expect as all the paperwork is done to be setting up even more affiliations. This is why I want to launch at SIGGRAPH, because there will be so many academics there to communicate with.

Pete: What else is going on?

Julian: I have a startup. Should I talk about that?

Pete: Yes, please.

Julian: Okay. A long time ago, I was the chief scientist of LEGO. Last year I got together with the former chief visionary of LEGO. Using my ideas about how people interact with tech, we decided that we should start to build play apps. Apps on iPads, but it won't be the kind of thing where you slide your finger around on the screen. You'll use your cognitive abilities to interact because the technology is smart enough now that we can pick up on how people are behaving instead of forcing them into the paradigm of being flat again.

Nuon Play is a corporation where we are developing apps based on these principles starting with play. One good way of playing is to just play with blocks. Little kids play with wooden blocks, and depending on how much money your parents have, you can play with plastic bricks. If you study child development psychology, these play mechanisms are essential for development. My contention is that we need to follow the same kind of approach in the digital world if we're going to work well with humans.

Nuon Play is following the same line of “being done with flat.” It's following the same line of looking at the future of how to interact with tech. But it is a commercial startup as opposed to the Center, which is a nonprofit startup.

Pete: Congratulations!

Julian: Thanks!

Plex Reflection Questions

by Peter Kaminski

I created these questions as starters for Plex conversations, and I realized they might be good reflection questions for Plex readers, as well. Please use or repurpose them as you wish. Send me an email, kaminski@istori.com, if you happen to end up with something written to share!

Your Story / Our Story

1. Tell me an anecdote from your life, either recent or from the past.

2. Tell me a memory or story about the Plex, OGM, CICOLAB, etc.

Your Project(s)

1. What project are you currently most excited about, and why?

2. Are there any collaborations or partnerships you can tell us about that are playing a key role in your current work?

3. How do you see your current projects evolving over the rest of the year?

4. Are there any emerging trends that are influencing your work right now?

5. What would you most like Plex readers to know about your project?

Current Events

1. What do you think are the most pressing global issues we're facing today?

2. What do you think is required for people to focus their attention on those issue?

3. Will we succeed in addressing them, or will we fail?

4. How do you think recent advances in AI will impact society in the near future?

5. What challenge would you most like to focus Plex readers on?

Reading / Thinking

1. What books, articles, podcasts, etc. do you find most useful recently?

2. What books, authors, thinkers, philosophers, beliefs do you find most timeless, and continue to come back to for inspiration or solace?

charles blass

Why Large Institutions Are Needed to Deal With Climate

by Douglass Carmichael

Certainly. Here's the revised version with those changes:

As the larger system we are part of finds itself failing, it is easy to see why people start looking for local strategies for survival. However, small local efforts, while short-term survival strategies, are unlikely to scale to the level of the global CO2 blanket. For several years, I have been clear that the normal group of organizations, corporations, and government agencies are also too small to affect the kind of change we need.

The first issue is the significant avoidance of fossil fuel burning. Any institution such as a government agency or corporation is too bound by law and contract to make proposals that make a difference. This is because one aspect of such proposals would be a direct attack on the originating institution.

Second is depowering financialization, which means crippling capitalist control and establishing new forms of work and reward distribution. A few months ago, I was exploring the idea that cultures, with their diffuse presence, are bigger than nation-states with their rigid borders. The borders prevent nations from acting outside their boundaries, and climate coping needs to operate more broadly than any nation-state, including the big three: China, India, and the US.

Reading Toynbee's Study of History suggests that cultures (civilizations) are the more powerful influences for serious change in law or philosophy. The spiritual orientations of leaders have a bigger influence than their ideas. This leads to the adoption of their views by the general population and success in the following history. Alternatively, where people avoid alignment with the weak spiritual orientation of the leaders, the societies collapse.

We have slight spiritual leaders in our time. Probably the last candidate that almost made it is John Kennedy, whose light has shrunk to that of a fizzling candle. People my age remember that his photograph was on the wall in the halls of the poor in all parts of the world. We need that kind of alignment with a spiritual feeling for the world. Otherwise, I am proposing, there is no possibility of humanity gaining a friendly grasp of the Earth we live on.

We need a seduction of the Earth by humanity. It will take modesty and a full use of our engagement to make this couple a success. In summary, it will take institutions as large as all of humanity, a reinvigoration of the best ideas and feelings spread throughout the religions of the world. This includes not just those that emerged with the big empires, but those of earlier people who lived on a few acres of land, fished and hunted, gathered and walked, sang songs and carved and painted, cared for each other, and the animals. The nation-state is, above all, an obstacle to such a return.

I want to raise a couple of very difficult questions. The Roman historian Polybius wrote that some issues are best dealt with by democratic governments and some others by authoritarian governments. Which is better, he argued, depends upon the issues being faced. When the issues are primarily national, democracy is best because it allows the issues to be expressed by various interest groups, setting the conditions for resolution. But if the problem is from outside, then a united government is best, with authoritarian control in order to have a united front.

The Romans actually voted some governments in and some governments out based on this contingency. His influence on the founding fathers of the US was not to focus on oscillation between appropriate types of government but on the principle of checks and balances creating harmony. This approach lost the critical edge that requires thinking. In trying to think this through, I concluded that climate change is in the category of transnational problems but noticed there was no obvious candidate to fulfill the authoritarian role.

Then along comes Trump. Could he seize on the climate issue to create a platform for his own quasi-authoritarian regime? (This is so unobvious. But remember the country and the world could fall into a highly chaotic state appearing even to Trump to be ungovernable). The hope is not that the authoritarian approach dominates all politics but that it has enough leverage to lead while the majority of the population works on local opportunities to increase local viability. They will do this anyway. The unknown is: can any kind of legitimated central government, transborder, emerge?

Heavenly Hydrangeas

by Ken Homer

Summer 1980–Bali

by Ken Homer

I was approaching the end of my four years in The United States Coast Guard. Despite the common misconception that us Coasties were a stateside lot, the USCG had bases in far flung ports. I was stationed on Saipan from ’78 to ’80.

I was a young man seeking adventure. My original plan was a trip with the Overland Tour Company—which was an outfit that used 4-wheel-drive school buses to complete a journey from Katmandu across Asia to London. You could do the other direction too.

My housemate had done this trip and it looked so amazing I decided that rather than take military transport back to the states that I would take the long way home… following the Silk Road through Asia. I got a copy of Lonely Planet’s Across Asia On the Cheap—a slim volume in 1980—and I put down my deposit for the journey. I was stoked!

But three months later some fellow called the Ayatollah Khomeini came to power in Iran scuttling my plans by closing that route off to me and all other travelers. I needed an alternative plan.

I swapped Across Asia on the Cheap for Southeast Asia On a Shoestring, where I planned to spend the bulk of my time with stops in India and Nepal and England before finally heading home.

I obtained my discharge on Guam. Got a little circuitous travel pay. Then, I added that to my lifetime savings which brought the total to $4,200 – some $16,000 in 2024 dollars. I bought an open-ended plane ticket from Guam to Manila to Hong Kong to Bangkok to New Delhi to London then back to New York. The cost was a mere $649.00.

My savings saw me through ten months. I ran low and sold my camera in Nepal, which gave me two months of expenses.

In my final months on Saipan, I read James Michener’s The Drifters. That book conjured such visions in my mind that I knew I needed to set a course for the magical isle of Bali. I arrived there in June.

Bali was indeed a most magical place. You could order magic mushroom and sea turtle soup at any restaurant on Kuta Beach. Then, you could sit on the beach and trip out on the psychedelic sunsets. Mushrooms were a fave of mine but you need to allow a few days between trips.

I got the first massage of my life on Kuta Beach from a tiny old woman whose fingers were like spring steel. I’d never experienced anything like it. Between the heat of the sun and her technique, my body melted into the sand like the waves lapping the shore.

There are temples everywhere on Bali. My understanding is that the Balinese have no word for “art” in their language. Yet the entire island is an art project. There are carved figures and gorgeous arrays of food and flower offerings to the Gods nearly everywhere you look.

The people were warm and hospitable. Slow to anger and quick to smile. They have a profound reverence for nature. It’s a culture where the world is alive. Rocks, trees, water, mountains, air, and fire all are infused with the sacred.

Great food was abundant and cheap. Each meal I ate looked like a work of art. All the day-to-day details of ordinary life seemed to be ritualized and beautified I stayed for a month in this wonderland. But there was trouble in paradise for me. I traveled to the north shore which was rural—Bali has undergone staggering amounts of development since 1980—I got to see paradise before it was paved!

I was in a tiny village the name of which is lost to me or maybe I never knew it. I stayed in a losman—a simple hut—one of five owned by a villager who rented them out for $5.00/night. Each was modest yet artfully built. There was a communal toilet a few yards away.

I’d gone hiking in the interior one day, marveling at the fecundity of life in the rainforest. Little did I know that I’d been bitten by a mosquito carrying a terrible tropical disease that would lay me low.

I went to dinner at one of the two restaurants in the village center. I ordered my meal and by the time it arrived I had gone from feeling well to being sicker than I’d ever been. I apologized to the waiter. Somehow, I managed to stagger back to my hut where I collapsed in the worst fever I’ve ever experienced.

In the hut next to mine were two German women. They were angels, looking in on me each day, and bringing me bottles of fresh water that was safe to drink. They had a thermometer which is how I know that my temperature surged to 104.7ºF—dangerously high! My brain was literally cooking inside my cranium, but I could do nothing as I was too weak to move.

There was no medical help to be had. At least there were no western doctors. Had I known then what I know now, I would have asked for a local healer—but at that time I was too ignorant.

The fever made me delirious. There were alternating hours of laying on top of the sheets and sweating profusely, followed by hours of laying under the sheets with all of my clothes and anything else I could find to warm me as my teeth chattered and my body shook violently.

In my moments of lucidity, I fell into despair. I was 10,000 miles from home. I was all alone—no one knew me. I wished with all my being to be home. I was sore afraid that I was going to die.

In my moments of delirium, I thought I heard my mother calling to me even though she’d been dead for 14 years. That’s how I knew I was hallucinating.

It took eleven days for my fever to break. I awoke at some point on the eleventh day and realized the worst had passed. But I was so weak that when I walked to the toilet, I collapsed on the way back. I laid in the dust until another lodger came by and was kind enough to help me stagger back to my hut. I had lost 20 pounds and likely countless neurons perished during that fire in my brain.

A month later while in Singapore, I got a horrid sore throat. I went to the hospital where a beautiful young doctor peered into my mouth. She frowned and put her hand on my shoulder and said “Aw” with such genuine empathy that I instantly started to feel better. But it’s possible that I was just falling in love a little, dazzled as I was by her pulchritude and her caring.

I recounted my illness on Bali and asked if she had any idea what it might be. She speculated it was one of two things. Either I’d had dengue fever or malaria. How can I know what it was? She said if it was dengue fever it’s over and done with. If it comes back, then it’s malaria. I’m grateful that It never came back.

Ken Homer • March 2024

charles blass

Thank you for reading! The next edition will be published on 17 July 2024. Email Pete with suggested submissions.

Grateful appreciation and many thanks to Charles Blass, Douglass Carmichael, Patti Cobian, Wendy Elford, Ken Homer, Todd Hoskins, and George Pór for their kind contributions to this issue.